My startup became public and it only took me about 25 minutes to complete it. I do not remember what the company does, even though I do not think it matters? I own 16 percent of the site, but after making some hasty decisions about a legal battle and choosing to set up a local office in India, the company has virtually no cash left. Users love us though! So the future is bright for … whatever our name is. It does not matter. In a moment I’m starting over and trying something else.

I’ve spent too much of my day today playing Startup Traila new browser game created by the tech policy site Techdirt and Engine, a DC-based boot trade group. The two organizations created the game, which Techdirt’s Mike Masnick puts it to give people a little insight into the kind of political decisions startups have to make and why they are rarely as easy as they seem. Especially for small businesses that do not have the seemingly endless resources like a Google or an Amazon.

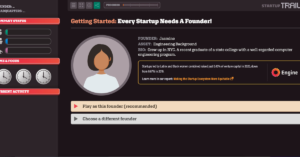

At the beginning of Startup Trail which certainly has an echo of Oregon Trail, and Masnick told me that the debate over whether dysentery should be involved went all the way through the night before launch – you choose the kind of founder you want to be and where you want to be located. I chose Mike, who has wealthy connections, graduated from “an elite institution with a reputation for showing startup founders,” and sounded pretty much like most of the Stanford student startup founders who ran around Palo Alto. I chose to set up shop in “University Park,” where there were plenty of cheaper talent, but not as many investors as I would have found in “Big Tech Valley.” In fact, I never got to choose what my business does, because it does not seem to matter. Most startups deal with the same things.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23421125/Screen_Shot_2022_04_27_at_4.50.14_PM.png)

From there, my life as a founder became an endless series of questions, each fighting for my money, my time, and my team’s talent. Every time I made a choice – to raise money instead of hiring or to focus on content moderation instead of spending my limited capital on working on them – the meters on the left side of the screen would move around. One tracked my financial health, another my user growth, a third my technology and talent. And beneath them all, three slowly disappearing clocks reminded me that both time and energy are limited, and I can not do everything at once.

The game’s major point becomes clear pretty quickly: doing the right thing is hard, even when it’s obvious what the right thing is. (And it’s usually not obvious.) Although I had come across what seemed like easy choices – like telling users when I submit their information to law enforcement – I had to reckon with the time, money, and potential disadvantages of that decision. (Choosing a fight with the FBI is a bit of a waste of time.) When I decided not to worry about the competition because any startup CEO tells me they are not worried about competition, my competition eventually crushed me. I had to decide who I was going to raise money from and how much I was going to travel, all with no idea what geopolitical or regulatory issues might arise later. I withdrew from Brazil instead of complying with a terrible new regulation, but I’m still not sure I did the right thing.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23421126/Screen_Shot_2022_04_27_at_4.49.56_PM.png)

Techdirt has worked on games like Startup Trail before, mini-simulators were meant to help people understand the complexity behind news issues. “We discovered that games as a concept are a really interesting way to explore difficult ideas, difficult political ideas and also play with the future in general,” Masnick told me. In far too many cases, he said, “everyone has their position and they’re really dug in.” But when it comes to games, “just from the premise, you say, ‘OK, put yourself in this other role. What would you do?'” Techdirt ran a simulation, for example, to learn how disinformation can affect the 2020 election, and got some … disappointing results. And it is Magic: The GatheringCard games based on a CIA training program are still a fun way to spend an evening. Going forward, Masnick said the team is working hard on an even more intense game dedicated to trust and security issues.

When you get to the end of the game, you can share how you did. You get points for each category plus a total score out of five unicorns. (I have four unicorns, not to brag.) And finally, if you’re lucky, you can decide what to do: go public, get procured, stay private, or hire another CEO and go out on a limb. yacht somewhere.

Masnick said that if there is a perfect way to play the game, then he does not know what it is. “I know exactly how it’s scored, I have access to it and I have no idea what the best way through is,” he said. As I have played through a few times, most roads end up in ruins. You run out of money, you get squeezed by a competitor, a legal issue catches up with you and takes you down. In a way, I guess the “patent trolls got you” is the 2022 version of dying of dysentery.